Author: Biatur Mandia, MEng

Table 1: Low temperature domestic hot water system

Benefits Challenges

Savings in energy consumption KW h Hygiene Legionella

Low Heat loss Comfort Temperature

Low-risk Scalding Design & Implementation

Low-Temperature DHW systems operate in the range of 40° to 55° Celsius. This presents several key benefits that help to reduce the carbon emissions of the system, and therefore, contribute to achieving the Net Zero target by 2050.

On the other hand, low working temperatures present important challenges due to hygiene and reduced comfort. The hygiene requirements are associated with the control of Legionella, a potentially fatal form of pneumonia. Specific guidance for the control of hot water systems is provided in the Health and Safety Executive Approved Code of Practice (ACOPL8) and its associated regulations, HSG274 Part 2. ACOP L8. Some key guidelines are summarised in table 2.

Table 2: Legionella requirements Comfort recommendations

Storage >60 Shower > 40

Recirculation pipe >50 Kitchen Sink > 45

(55 for vulnerable people) Waiting Time < 10 s

The legionella safety requirements differ in situations. These largely depend on the volume of water required during peak times. Generally, household applications have low water volumes and can be more flexible in terms of temperature range and safety requirements. These applications often do not need recirculation and storage when instantaneous heaters are employed.

Commercial applications have high volumes of hot water. These require high working temperatures to satisfy the recirculation requirements. The consumption of a commercial DHW system can be categorised as follow.

• Energy to heat the water

• Energy to reheat secondary return (recirculation)

• Pump energy

A lot of research is investigating the feasibility of having low-temperature return systems. There is a growing interest that instantaneous water heater could soon reduce the outlet temperature to 50°. Instantaneous heaters are considered “low risk” for legionella by the H&S executive and new guidelines are due to be published on the CIBSE Knowledge Portal. A successful low-temperature DHW system was implemented at Great Ormond Street Hospital. This was achieved by having a rigid disinfection process in place. Copper-silver ionisation measures were used to clean the water of the system. The working temperature was set to 43° and no legionella issues were found.

Practical example: recirculation of a low temperature DHW system powered by hydrogen

In the proposed example, hot water is utilised on-demand, and thus, eliminating the need of storing high-temperature water, as for ACOPL8. The system is adjusted to include copper-silver ionisation which further reduces the risk of legionella. The working temperature is set to 43Æ. In the proposed system, the legionella risk was minimised by eliminating any major water storage. The appliance can supply temperatures in the range of 42-45 degrees without affecting the efficiency of the water heater. This approach can be considered as the first step towards Lean Energy and the elimination of hot water storage often referred to as waste or “Muda” in Lean Japanese principles.

Figure1

The working principle of the system is shown by the schematic diagram in figure 1. The water heater is powered by the hydrogen & Natural Gas blend. This reduces the carbon emission of the appliance. The heater also modulates the heating input according to the desired outlet temperature. For instance, if the heater has a gross heating output of 58.3kW and a 13:1 turn down ratio, this can potentially modulate down the heating to 4.4kW, thus enabling massive savings in the secondary return system (recirculation) while still providing the desired temperature. The heating process is optimised and programmed using a high-tech processor and PCB; performance charts are programmed to operate the appliance at maximum efficiency. Advanced control strategies can enable significant energy efficiency improvement of the DHW production systems and generate carbon savings.

Heat loss savings of low-temperature system vs high temperature

The energy losses in supplying domestic hot water can be categorised into two main groups:

• Energy loss in the heating process

• Energy loss in the distribution and storage.

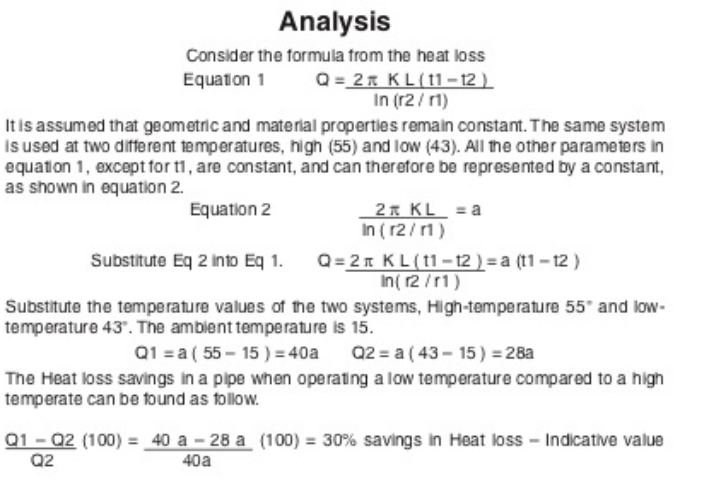

Low-temperature DHW can reduce the amount of heat loss of the system. The following analysis shows the heat loss savings of a pipe distribution network.

Figure 2: Recall: Heat Loss in a pipe

The general formula for calculating heat loss in a non-insulated pipe can be shown as follows.

Q = 2 p K L ( t1 – t2) / ln ( r2 / r1 )

Where:

K = the heat transfer coefficient of the pipe material;

t1 = Temperature inside the pipe;

t2 = the outside temperature of the pipe;

L = the length of pipe;

r1 = inner radius of the pipe;

r2 = outer radius of the pipe;

ln = natural logarithm

Carbon savings of the proposed system

The following example considers a business case for a small/medium size application. The analysis shows the savings in carbon when a low-temperature system powered by hydrogen blends is employed. The savings in heat loss previously calculated were also added in the analysis. The hydrogen blend was assumed to start in 2025. The results have shown carbon savings in the range of 33% and 50% compared to a high-temperature system. The exact value would depend on the mass flow rate of the proposed system and other parameters. Low-temperature systems are effective ways to reduce the carbon footprint and Hydrogen is currently undergoing unprecedented political and business momentum. Gateshead has become the first UK community to receive hydrogen blends via the public natural gas network. This growing trend is very likely to continue over the next years. The carbon savings of the proposed system are considerate and as a comparison, these equate to the annual average carbon emissions of 20 cars. With thousands of commercial buildings in the market, such implementation would have a very positive impact on the environment and our future.